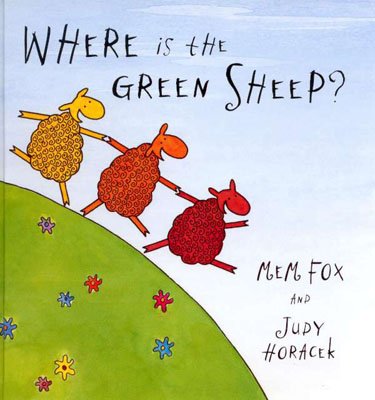

Where is the Green Sheep?

Written by Mem Fox and Illustrated by Judy Horacek

There are red sheep and blue sheep, wind sheep and wave sheep, scared sheep and brave sheep, but where is the green sheep?

Listen to Where is the Green Sheep?

The Story Behind Where is the Green Sheep?

Where is the Green Sheep? is my second most famous book, after Possum Magic. Children have been known to receive it up to three times on their third birthdays which is great for Judy and me, but puzzling, to say the least, for the children.

‘Here is the blue sheep

And here is the read sheep.

Here is the bath sheep.

And here is the bed sheep.

But where is the green sheep?…’

We have a green sheep toy in house which we hide from each other from time to time, so one of us has to say: ‘Where IS that green sheep?’ We might find it days later, sitting sweetly the wheelbarrow in the shed, or tucked behind the cereal in the pantry cupboard, or under a cushion that’s rarely moved, or behind the spare toilet rolls in the loo.

Here’s a hilarious ‘Where is the green sheep?’ clip made by Penguin’s Marketing and Publicity department. It makes me laugh aloud every time I see it.

Here’s the story of its creation, from a speech I gave at the International Reading Association in the USA.

Those who have heard me before will know how much I detest writing picture books. You will know that I loved writing this speech because it kept me from having to writing for children! Writing picture books is not what I live and breathe, in my daily life. It nibbles merely at the edges of my life. If it took up any more of my life it would be the death of me. Believe me, you wouldn’t want the misery of writing for the very young to take up any more than 10% of your time either, unless, of course, you enjoy being on Prozac and you look great in a strait-jacket. Writing picture books is madness. It’s hell on earth. Let me take you through the process so you can weep along with me and send me sympathy cards afterwards.

The question most often asked of authors, the time-honoured question is: ‘Where do you get your ideas from?’ Morris Gleitzman, the hilarious Australian children’s author, tells children that he find his ideas between the Vegemite and the honey on supermarket shelves. And they believe him.

I find my ideas from my own life and from books, which are after all part of my own life anyway. I find them when I’m not looking for them. They come to me, not I to them.

Let me take as an example, my latest picture book: Where Is The Green Sheep? Where did the idea come from?

In mid-2002, when I was trying to avoid writing a children’s book, I browsed the web-site of Judy Horacek, the cartoonist who had illustrated my parent book: Reading Magic. She has new cartoons on her web-site every month, and sometimes gorgeous, diminutive water colour paintings which she sells. In June 2002 I found on her website a little water colour painting of a sheep: a heavenly, pale green, woolly sheep standing in a dark green field. I fell in love with it.

Judy had always wanted to write and illustrate a picture book and I felt immediately that this divine green sheep would be a great main character, so on June 2nd I wrote to her.

Dear Judy,

The Green Sheep is a brilliant starting character for the kids’ book that you are going to write one day if I have any influence on you whatsoever.

Why is it green? Where does it live, and does it live all alone? Does it perhaps have hopes of being a red sheep instead? Does it set out on a quest to change its colour? Is it thwarted in its quest: at one point becoming unbecoming stripes, for example, by accident? Does it find a new colour and happiness or does it decide that after all being green is what it loves best?

There: you have the first draft. It’s yours.

With love,

Mem xxx

She was excited. She sent back a long answer in which she said, among other things: ‘…write a children’s book yourself for me to illustrate, I’d love that.’ I was wild with excitement and felt like starting right away.

There followed a brief period of e-mailing, with Judy raving and saying she’d always wanted to work me, and me saying: ‘Well, why didn’t someone tell me ages ago?’ and our agreeing that we should indeed go along with the Green Sheep idea and see where it went.

But one of the many repugnant aspects of writing for little kids is finding a brilliant idea that will appeal to them—to the children—not just to the adults who’ll be reading the books aloud. I knew it would be easy to write a picture book about a Green Sheep that would please other adults, but I also remembered with dismay how fantastically difficult it is to write a picture book that will please children. I had to write a Green Sheep story that children would like.

After twenty one years of writing for children, I’ve come to appreciate that the books young children like best fall broadly into two categories: either short books with a pattern, based on rhyme, rhythm or repetition; or short books with a really good story. They don’t like nostalgia books. They don’t like first person books. And they don’t like long books. Stories, or patterns: that’s it.

I had decided to write a story on this occasion, rather than a rhythmic, rhyming, repetitive book, so I needed trouble for my Green Sheep. Without trouble there is no story. I needed a calamity. I needed a really great idea. Finding such an idea, or in my case more often NOT finding that idea, frequently causes me to feel I’m finished as a writer, that I’ll never write again. What’s worse is that I know from experience that the ideas have come to out of my own life, or they don’t work. People often suggest ideas to me—in fact people are always very ready with ideas—but the ideas have to be mine. And the Green Sheep, thank God, was mine.

I set out some broad ideas. I told Judy I saw it as a book for the very young, with hilarious but simple, very bright visuals that would present little kids with the different primary colours, and with stripes and squares etc., as well as exposing them to the ideas of loneliness and friendship. I said: ‘… It takes me 18 months to two years to get a text right but my mind will be on to this from now on. Who knows? It might be one of my miracle Quick-as-a-Wink ones.’ (It wasn’t, as it turned out!)

Before I go on, let me say immediately that it’s highly irregular and unusual for an illustrator and a writer to collaborate on a picture book in the way that Judy and I did. As a rule, I write the story alone, finish it alone, and send it to a publisher alone, without any pictures, without any illustrative ideas, and without any suggestion as to who the right artist might be. I trust the publisher, as writers must, to find the perfect artist with the perfect feeling and tone for that particular story, to ensure that the book works well as a whole.

Collaborating with Judy was a new experience for me. It wasn’t as lonely or as miserable as writing on my own. She made writing suggestions. I made illustrating suggestions, and we worked in real time on e-mail, back and forth, with Judy sending pictures by fax whenever she had any to show. It was invigorating. I loved it.

As I had warned Judy, the writing of write Where Is The Green Sheep? did take an astonishingly long time, almost a year to complete, even though it’s only 190 words and two of us were working on it together. It’s hard to explain what happens inside a writer’s head in those awful months (and sometimes years) of re-writing, but I’ll give it a try.

I’ll begin by reading the earliest draft of The Green Sheep that I could find—I believe it’s Draft No. 8; then I’ll read the book [again] as it finally appeared; and then I’ll show you what happened between Draft No. 8 and the book as you see it now: the journey we took; how we lost our way; how we once gave up altogether and went home, so to speak; and how we arrived, finally, at a totally different destination from the one we’d set out for two years earlier which why writers should never do story plans. Children in school should never do them either. One of the greatest maxims for writers is: ‘Why would I write if I knew what I were going to say?’ We learn what we will be saying by writing ourselves into it. We cannot know at the beginning what our end will be, or where.

Here’s Draft 8, in all its ghastliness:

Once there was a green sheep who lived all alone in a huge green field. One day a goat passed by. The goat stared at the sheep and the sheep stared at the goat. ‘Whoever heard of a green sheep?’ asked the goat. ‘You look really silly.’ And he ran away, laughing his head off. The green sheep was so upset she didn’t eat a thing ALL day. What’s more, she was so upset she didn’t hear the gate click open, she didn’t see the sheep come into the field, and she didn’t even notice the old grey ram with the scary horns. But she did hear: ‘The green sheep! The green sheep! Hip, hip, hoo baa!’ ‘Hello there,’ said the yellow sheep. ‘You’re perfect,’ said the blue sheep. ‘Just as I imagined,’ said the red sheep. ‘We’ve missed you,’ said the white sheep. ‘We’d almost given up,’ said the black sheep with a little sob. ‘Why me?’ asked the green sheep, who was secretly thrilled to be so admired. ‘To make our family complete,’ said the purple sheep. ‘You need every colour in the world to make a real family. Everyone knows that!’ ‘Three cheers for the green sheep!’ said the brown sheep. ‘HIP, HIP, HOO BAA! HIP, HIP, HOO BAA! HIP, HIP, HOO BAA!’ At which point the goat came by again. The goat stared at the sheep and the sheep stared back. ‘You all look REALLY silly,’ said the goat. ‘I BEG your pardon?’ said the old grey ram, lowering his horns. ‘Take no notice, said the green sheep. ‘What would goats know about families anyway?’ But the old grey ram was so wild he leapt the fence in a single bound and tossed that goat so high he was never seen or heard of again. ‘Three cheers for the grey ram!’ said the green sheep. HIP, HIP, HOO BAA! HIP, HIP, HOO BAA! HIP, HIP, HOO BAA!’ ‘Silly old goat,’ said the old ram, looking pleased with himself. And they all lived happily ever after, in their lovely coloured wool.

Now here it is, two years later, in its published form:

Here is the blue sheep

and here is the red sheep.

Here is the bath sheep

and here is the bed sheep.

But where is the green sheep?

Here is the thin sheep,

and here is the wide sheep.

Here is the swing sheep.

And here is the slide sheep.

But where is the green sheep?

Here is the up sheep,

and here is the down sheep.

Here is the band sheep.

and here is the clown sheep.

But where is the green sheep?

Here is the sun sheep.

And here is the rain sheep.

Here is the car sheep,

and here is the train sheep.

But where is the green sheep?

Here is the wind sheep.

And here is the wave sheep.

Here is the scared sheep,

and here is the brave sheep.

But where is the green sheep?

Here is the near sheep.

And here is the far sheep.

Here is the moon sheep.

And here is the star sheep.

But where is the green sheep?

Where IS that green sheep?

Turn the page quietly—let’s take a peep. . . .

Here’s our green sheep—fast asleep!

Draft No. 8 has 342 words and the Green Sheep as we now know it has only 190. 188 of those words have one syllable; one word: ‘asleep’ has two syllables; and one word: ‘quietly’, has three. A picture book should be under 500 words so 190 words was pleasing.

When we’re writing for the very young, brevity should be our goal. This sounds easy. After all, short texts look easier to write than long ones. How could there be more effort, people ask, in writing such a few words? Adults in bookshops occasionally complain about paying twenty five dollars for a picture book with 200 words, as if words had some kind of monetary value, and therefore the more the better—the fewer the cheaper. In my experience, frankly, it’s rare to be given credit where credit is overdue, for the ability to write briefly for the very young, because that’s the trick of it: ‘short’ does appears to be easier than ‘long,’ but the opposite is the case. ‘Short’ is the very devil itself.

The attention span of a young child isn’t very long, so for this age group a short text is always more effective than a longer one. Description has to be abandoned in favour of revealing characters and the trouble they’re in, and how they overcome it. The trouble with the trouble is, however, that it can’t be superficial. For a picture book story to become a classic—that is, to last long enough for the writer’s children to go on receiving royalties after the writer is dead—the trouble must be trouble on a grand scale. It must be the kind of trouble that works its way into the depths of children’s souls and makes their hearts sink into bleakness and despair. Momentary despair, of course!

Which brings us back to Dreadful Draft No. 8 of The Green Sheep. The greatest requirement for those of us who write for children is to develop the highest possible level of dissatisfaction with what we have written. Many amateur writers would have had early-onset satisfaction with Draft No. 8 and may even have sent such a draft to a publisher, as the final version, as the best they could do. Self-congratulation comes too easily to the amateur writer, and also to me, I must admit. But to have been satisfied with Draft No. 8 would have been tragedy. It never would have been published, and even if it had, it wouldn’t have sold, due to the low level of its ‘trouble.’

I re-drafted the story so many times a day that as I printed out each new version I’d have to write the time of day on the top so I’d know which draft was which: ‘Before breakfast. 10:00 am. 11:47 am. Post-lunch draft. 2:22 pm. Pre-dinner draft,’ and so on, till midnight. I’d read aloud, and read aloud, and read aloud the story, to hear the rightness of the words and the wrongness; and as I listened to my own voice stumble and falter I would change things, big and small, like the entire plot; or taking out a single syllable in a particular phrase so a line would read smoothly instead of hiccupping along like coughing tramp.

How can I illustrate this kind of nit-picking in the drafting process? Let me move away from the Green Sheep for a moment and take the first line of Koala Lou as an example. In the early drafts it went like this: ‘There was once a baby koala, so soft and perfect that everyone who saw her loved her.’ Now you don’t need a very fine ear to hear that there are too many syllables in that line: ‘There was once a ba-by ko-al-a, so soft and per-fect that ev-ery-one who saw her loved her.’ Oh it’s awful! There’s no rhythm to it at all! It has far too many syllables.

So I changed ‘everyone’ to ‘all’ which wiped out two syllables right away: ‘There was once a baby koala, so soft and perfect that all who saw her loved her.’ I was very pleased with myself until I looked at perfect: ‘…so soft and perfect…’ I didn’t like the ‘er’ sound in perfect. Nor did I like the ‘ect’ in ‘perfect’: it was too harsh and scratchy. Nor did I like the two hard syllables in ‘perfect’. They jarred in an otherwise lovely sentence that rolled along the tongue with sounds like: or, uh, o, ow, oh: ‘There was once a baby koala, so soft and perfect that all who saw her loved her.’ So I changed ‘perfect’ to ’round’ and knew, then, that it was right: ‘There was once a baby koala, so soft and round that all who saw her loved her.’ All the words were round-sounding and the choice of those sounds had helped to ‘paint’ the koala round.

How did I know how to make these changes, and how did I know what changes to make? How did I know about the rightness of rhythm, and the riddle of syllables? How did I know that sounds in a sentence can paint pictures in words? These things cannot be taught. No one can teach them. No one taught me. No one, thank God, killed the language or mutilated the literature I loved by hacking it into little pieces and teaching it to me little bit, by little bit. No! I was instead blessed many times over by having people read aloud to me. My mother and my father, my teachers and my professors all poured into my willing ear the finest prose, the most glorious stories, the most uplifting verse, and the most inspiring drama written in the English language. My ear was my teacher.

So you can imagine—can’t you?—how distressed I am whenever I hear of adults who interact with children daily, but never read aloud to them, in homes and child care centres, in school and libraries. Children depend upon us for their future. We have to read aloud to them. There is no choice. We have to allow their ears to be their teachers. As we read to them they will learn about language, and all the ways of using it, and about life, and all the ways of living it. How can we not read aloud to the children in our lives?

A moment ago I was talking about drafting, then somehow I leapt on to my favourite hobby horse: reading aloud, and galloped a million miles away from away from where we were. Forgive me! Let me return to The Green Sheep, and to that famous Draft No. 8. It was short enough, certainly, at 342 words, and there was trouble in it, of a sort, but what child or adult reader could care less honestly, about a goat laughing at a sheep because it was green? The trouble with that story was that the trouble IN that story would never have worked its way into the depths of children’s souls and made their hearts sink into bleakness and despair, even though being laughed at is a universal theme and a universal dread. The trouble in a story has to be so serious that children think it’s the end of the world. They have to be utterly, utterly dismayed before we allow them to soar with thankfulness when the trouble is finally removed, and everyone lives happily ever after.

Judy and I re-wrote and re-wrote the story, seeking the elusive magic of trouble and not finding it. In the end we killed the Green Sheep stone dead: the story, that is not the sheep itself, although I do remember writing an e-mail heading to Judy Horacek that said: ‘Green Sheep to abattoir [slaughterhouse]?’

On June the 22nd 2002, three weeks after we’d first had the idea of writing a book about a Green Sheep, I sent this e-mail to Judy:

‘Please don’t read the latest draft of The Green Sheep. I have crucified it. It is horrible. All the humour with the goat is gone and must be restored. It is bland. It says nothing. It does nothing. It is nothing. This is a morning-after realisation.

‘I never share drafts as regularly as I have done with you, in order to preserve the fiction that I am a genius. I should stop sharing. I can’t help myself.

‘I have found over the years that drafts often take ten steps backwards before they can be reassessed and re-written so they can move two steps forward. It is endlessly depressing and makes me realise yet again why the writing of picture books is so detestable. Who in their right minds would put themselves through this if they could avoid it?’

At that point in my life I went overseas to work, and then to attend the third wedding of my middle sister in Italy. The holiday was a circuit-breaker. By the time I got back home in late July I had begun to suspect that the Green Sheep story was beyond resurrection. This was confirmed when I saw it afresh with all its faults and imperfections. ‘I couldn’t have written this,’ I said to myself. ‘I’m Mem Fox.’ But the story was indeed mine. And it was indeed dead.

Unbeknown to me however, there was still a tiny breath of life left in the poor old Green Sheep. It must have gasped every so often in my filing cabinet, in its struggle to keep hope and itself alive.

In late August 2002, the day after I had given a presentation on the need for rhyme, rhythm and repetition in the books for babies, I was in the shower, late as usual, thinking about my work as usual, and what I had said the day before. I remembered the joy my husband and I had had reading Dr Seuss books to our daughter Chloë, and how she had learnt to read at four and half without a single lesson. I began to recite in my head: ‘I do not like green eggs and ham, I do not like them, Sam-I-am.’

Green eggs and ham! Green eggs! Green sheep! All at once, in the miracle of the shower, that most creative of places, I had the entire concept of Where Is The Green Sheep? Out went the story of the Green Sheep, in came a rhyming, patterned quest for a Green Sheep! Should I run out of the shower stark naked and soaking wet, I wondered, and drip the idea all over my desk before I forgot it, or should I risk finishing the shower first and trust my menopausal memory? I trusted my memory. At 6:28 pm that day I sent a wild e-mail to Judy Horacek:

Dear Judy, Two things happened today, worthy of our burgeoning partnership. First, I was in the shower when I had such a clear and sudden vision of a new direction for the Green Sheep that I could hardly finish my shower. Let alone dry myself and get dressed before the mad exciting rush for pencil and paper.

The second thing that happened was that Malcolm and I drove miles into the country to a nursery to buy an apricot tree for our back garden. There are several varieties of apricot but the one that came with the highest recommendation was called literally ‘Story’s Improving’. Mad name for an apricot but it was A Sign, was it not?…

And here’s the new improved version of the story [which] came from apparently nowhere, although it was of course from my caught-off-guard, relaxed and soaking sub-conscious… The ‘sheep’ adjectives can be changed to anything you or I like, so long as the rhythm stays the same and the rhyme scheme remains A/B/C/B. Imagine reading it to a baby…

A year later we were still fiddling with it. We had a pro-forma so we wouldn’t have to write every word, just fill in the blanks. But even though the four line concept remained the same, the apparently simple text drove us crazy. The difficulties were many and various.

First, babies don’t know much outside their own little world so the nouns like moon and star, the prepositions like up and down, and the adjectives like thin and wide had to be simple enough for babies to understand. And all the words in the story that preceded the word sheep, as in moon sheep/ star sheep/ train sheep/ car sheep had to be one syllable to keep the rhythm constant—and we discovered early on that one-syllable words, like a good man, are hard to find.

To add to that difficulty, each four line verse had to have two pairs of items which had an obvious connection to each other like wind sheep and wave sheep in one pair; and scared sheep and brave sheep in the other pair. And although there was no similarity in the pairs: wind sheep and wave sheep have nothing in common with scared sheep and brave sheep, they did have to connect in the A/B/C/B rhyme scheme, as in: Here is the wind sheep, And here is the wave sheep. Here is the scared sheep, And here is the brave sheep.

These petty restrictions caused a great deal of teeth-grinding. At a desperate moment in the drafting process Judy sent me this entirely unsuitable, not-for-babies verse. Here is the song sheep, And here is the red sheep. Here is the bong sheep, And here is the dead sheep.

And finally there was the problem of the Mem Fox ‘signature’ of a bonding-at-bedtime ending. The early drafts of the final verse didn’t have the essential element that I now recognize as ‘solace.’ The last verse used to say: Where IS that green sheep? Let’s turn the page softly, and take a peep. . . . Here’s the green sheep, Fast asleep…!

It was re-written many times. In the end, a single word provided the solace of togetherness in the last lines—the use of ‘our’ instead of ‘the’: Where IS that green sheep? Turn the page quietly—let’s take a peep. . . . Here’s our green sheep, Fast asleep…!

I can’t believe I’ve spoken for an hour on the writing of a book with only 190 words. I bet you can’t believe it either. At least now when you read Where Is The Green Sheep? you’ll realize exactly what hell it was to write, and I hope, what absolute heaven it is to read aloud to the darlings in your life.

Judy and I receive lots of hilarious stories and photos about Green Sheep birthday parties. Cameron is one of millions of fans of Where Is The Green Sheep? He is absolutely besotted with this book, according to his parents, Deb and Rob, who sent us these hysterical photos of Cameron’s 1st birthday party in 2009:

Age Group

1+

Publishers

Penguin (Australia)

HMH (USA)

First Published

2004